AS THE WHITE HOUSE PULLS AWAY FROM CLIMATE PLEDGES, AMERICAN COMPANIES STEP UP

This may be the year that a presidential candidate who called climate change a “hoax” took office. It may be the year that the commander-in-chief announced he would withdraw the United States from a landmark global commitment to limit climate-warming emissions.

But it’s also the year that hundreds of American corporations and investors vowed to cut emissions—despite these presidential actions—joining a surge of companies around the country and world that have made it increasingly and publicly clear that they’ll take specific steps toward lowering their atmosphere-heating carbon emissions.

“There’s a growth, a momentum, a steady increase in the effort across the board, from various organizations, toward working on reducing their carbon footprint,” said Jayashankar Swaminathan, a professor at the University of North Carolina Kenan-Flagler Business School and an expert in global operations and supply chains. “It’s not a phenomena that’s just happening in the last year, but it’s fair to say it’s picking up in the U.S. lately.”

President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accord—the agreement reached in 2015 by nearly 200 countries that committed to cutting carbon emissions, and reaffirmed with foreign ministers at the United Nations Sept. 18—may have provided a spark, a new awareness that the private sector would instead have to do the job itself.

We Are Still In

Days after Trump’s announcement in June, a group led by former New York City mayor and Bloomberg L.P. CEO Michael Bloomberg launched a campaign—dubbed “We Are Still In”—in which hundreds of companies, investors, educational institutions, cities, and states announced they would “pursue ambitious climate goals.” In the group are dozens of companies with more than $100 million in annual revenues, including huge names—and huger revenues—from Amazon to Walmart. Altogether the group represents roughly a third of the country’s $18 trillion GDP.

“Together, we will remain actively engaged with the international community as part of the global effort to hold warming to well below 2℃ and to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy that will benefit our security, prosperity, and health,” the group wrote, shortly after launching.

“Together, we will remain actively engaged with the international community as part of the global effort to hold warming to well below 2℃ and to accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy that will benefit our security, prosperity, and health,” the group wrote, shortly after launching.

By “prosperity,” of course, the signees mean the broader financial well-being of the country. But there is, perhaps, an additional nuance to the word.

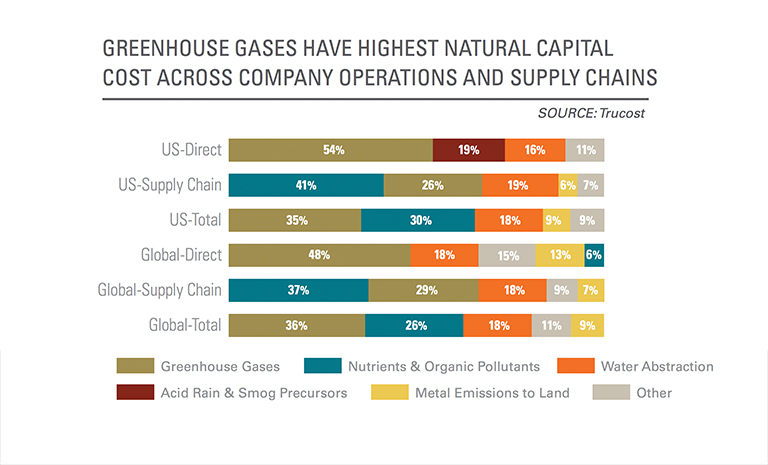

Under the Paris agreement, the world’s countries agreed to limit greenhouse gasses in an effort to keep temperatures to within two degrees Celsius above preindustrial times—the amount the international climate community has concluded will prevent the most devastating impacts of climate change.

To hit that target—or, even better, keep temperatures well below the two-degree target—the world needs to stay within a “carbon budget.” That is, the world needs to limit its carbon emissions by about 1,000 gigatons to have a good chance of meeting that goal. At least. (There’s some disagreement about the actual number.) Human-caused emissions total about 50 gigatons a year and that number is projected to go to more than 56 gigatons by 2030. That gives us 20 years or fewer. The U.S. government’s Energy Information Agency said in its latest forecast that global carbon emissions will grow 16 percent by 2040.

A relatively small number of corporations, mostly in the energy sector, are responsible for the bulk of those emissions.

“As the world’s largest source of emissions, the corporate sector has a clear role to play in the transition to a low-carbon economy,” according to the World Resources Institute (WRI), a global environmental group that works with corporations to outline carbon-related commitments.

And, indeed, meeting the targets under Paris will require the voluntary help of the private sector. Bloomberg said, in a declaration to the United Nations, that corporations, along with U.S. cities and states, will do what they can to meet the country’s pledge of reducing carbon emissions by 26 percent by 2025.

Making Supply Chains More Efficient and Leaner

But corporate commitments aren’t simply gestures of goodwill or part of larger global pledges, significant as those may be. Corporations are increasingly realizing that shrinking their carbon footprint—finding efficiencies deep in their supply chains—makes sense for the bottom line now and for their long-term survival.

“If you look at the most successful companies in this area, they view it not as an obligation, but as an opportunity to improve their processes. It’s more about making their supply chains more efficient and leaner,” said Swaminathan.

“If you look at the most successful companies in this area, they view it not as an obligation, but as an opportunity to improve their processes. It’s more about making their supply chains more efficient and leaner,” said Swaminathan, who is working on a report that looks at different approaches that companies use to improve their supply chain efficiency. “The successful ones aren’t doing it to be compliant. They are looking at their processes and analyzing them and optimizing them, and, as a result, getting savings or a better product.”

The list of companies embarking on these efforts has mushroomed in recent years. Microsoft in 2012 said its business would become carbon neutral by the end of the year. (It achieved that target, and has every year since.) Walmart said in November 2016 it would get half of its energy from renewable sources by 2025. McDonald’s has made commitments to buy beef from sustainable sources and use all fiber-based packaging by 2020.

Of the world’s 500 largest companies, 80 percent have set emissions reductions goals, according to WRI. But critics including WRI itself, say many of these aren’t meaningful because they’re not as ambitious as they need to be. The U.K.-based group CDP, formerly called the Carbon Disclosure Project, reported that of the more than 2,400 companies that responded to a questionnaire on climate change in 2015, only 44 percent had set emissions reductions targets.

A report last year by an initiative called Science Based Targets— a collaboration between CDP, WRI, and two other groups — said many of the companies failed to set specific or meaningful emissions targets. Most of the world’s top 70 corporate emitters, the report said, had failed to set adequate targets or any targets at all.

But that situation is improving. This month 300 companies committed to setting these “science-based” targets, in line with the goal of keeping temperatures well below two degrees Celsius. Fifty of those are U.S. companies—more than any other country.

“It shows that companies are stepping up to align their strategies with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement to tackle the global challenge of climate change,” said Alberto Carrillo Pineda, the director of the Science Based Targets project and renewable energy procurement at CDP. “Why are they doing it? Because it makes solid business sense. Companies that set science-based targets benefit from increased innovation, reduced regulatory uncertainty, strengthened investor confidence and improved profitability and competitiveness.”

The Three “Scopes”

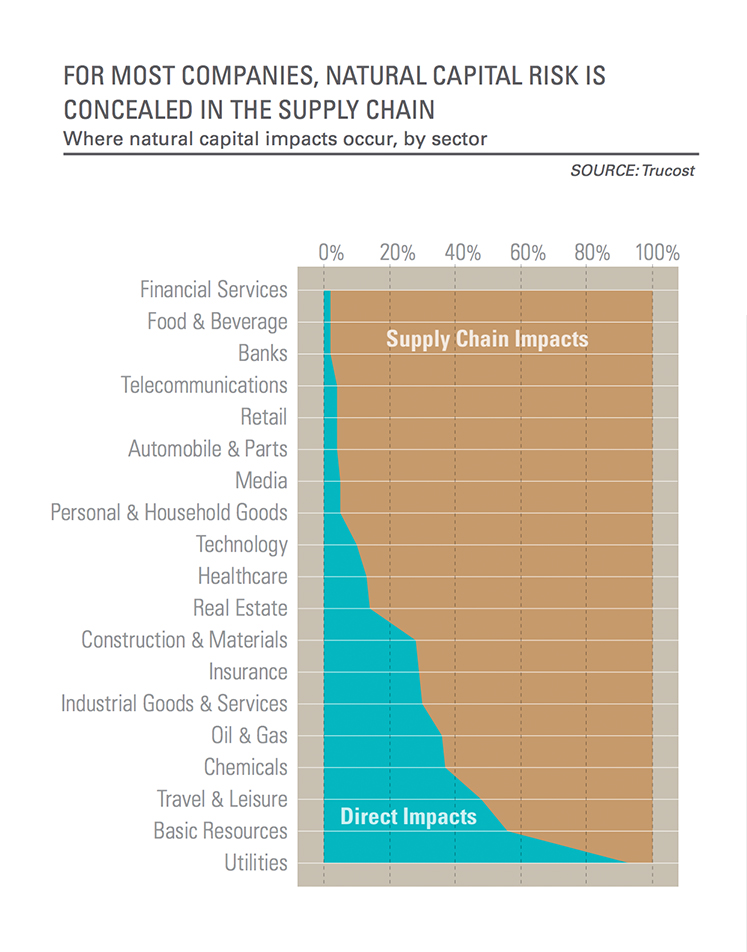

Companies have increasingly realized that reducing their carbon impact means looking beyond the emissions tied directly to the their operations. Under an initiative called the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which is overseen by WRI and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, corporations measure their emissions under three “scopes.”

Scope 1 emissions are those tied directly to their operations. Scope 2 are those tied to companies’ purchasing of electricity and steam. Scope 3 are tied to suppliers in their value chain. These Scope 3 emissions often represent the biggest source of a corporation’s overall emissions—but they are much more difficult to control and account for.

“Most companies are highly outsourced,” Swaminathan said. “So if you really want to show a huge benefit, you have to focus on your Scope 3 emissions.”

In 2011, the Greenhouse Gas Protocol released a reporting and accounting standard that became the only internationally accepted method for tracking these supply chain emissions—and provided the benchmark for companies to dive into their supply chains.

Walmart, a leader in corporate sustainability efforts, is one of these companies. In April 2017 the company, better known for pressuring suppliers to lower costs, would reduce its Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 18 percent by 2025, and asked its Scope 3 sources—its suppliers—to cut 1 billion metric tons of their emissions by 2030.

That was months after Trump took office and his administration began unraveling climate-related standards.

“There are a few dimensions to these sustainability efforts,” Swaminathan said. “One is the regulatory environment—the government saying you’ve got to get so much abatement or reduce your carbon footprint or pay penalties. Obviously that’s been relaxed under this administration. But at the same time there are the market forces—looking at what consumers want, what your competitors are doing and looking at the economic values.”

Citation for this content: MBA@UNC, UNC Kenan-Flagler’s online MBA program.